by Jerry Cornfield, Washington State Standard

February 13, 2026

Two members of the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission are pushing back on newly surfaced allegations that they shunned government transparency laws and appeared to have colluded with the leader of a wildlife advocacy group on policy matters.

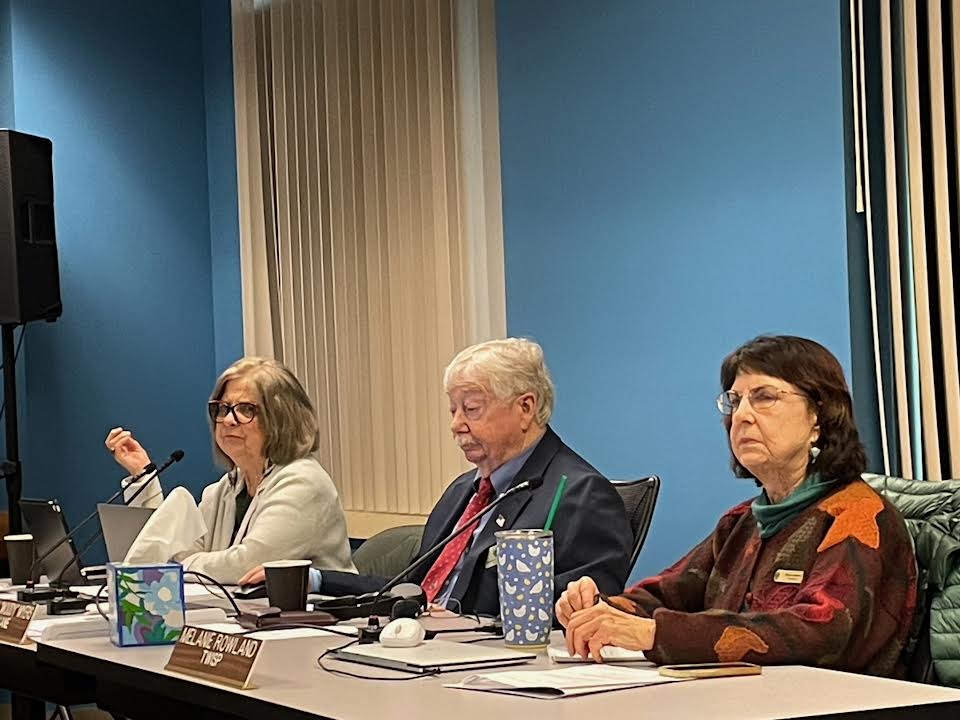

A scathing 10-page memo says the behavior of commissioners Lorna Smith and Melanie Rowland posed “serious risks” to the state Department of Fish and Wildlife, “especially when it comes to avoiding a conflict of interest and favoritism.” The report also scrutinizes a former commissioner Gov. Bob Ferguson chose to replace on the panel last year.

It is the latest twist in a multi-year drama involving the commission, which is often a battleground for groups fighting over how far the state should go in protecting wildlife or allowing for hunting or fishing of various species. A separate probe ordered by the governor, looking at whether commissioners violated open meetings and public records laws, remains underway.

Department of Fish and Wildlife Director Kelly Susewind had a top staffer prepare the newly released memo in May 2025. It was shared that month with Ferguson’s chief of staff and only became public this week through a records request by the Standard. Susewind’s move was unusual, as the commissioners oversee his department and he answers to the panel.

The report flags concerns about the named commissioners’ “tight relationship” with attorney Claire Davis, the president and chief executive officer of Washington Wildlife First.

While there are no transcripts of their frequent private meetings, the memo’s author said it looks like they may have been “propagating an agenda” in line with the advocacy group’s policy priorities. Davis’ group, meanwhile, has been calling for Susewind to be removed from his job.

Rowland, Smith and Davis are blasting the memo, saying it is riddled with false and defamatory statements that harm their reputations. The commissioners worry it could unfairly influence the ongoing investigation.

Smith and Rowland each said they first saw the document Feb. 2 when told it would soon be released as part of a public records request.

It “is replete with assumptions, inferences, unsupported accusatory opinions, and incorrect conclusions,” Rowland wrote Susewind on Feb. 9.

Davis said Knoll “recklessly makes allegations of misconduct against me without any evidence of wrongdoing.”

Francisco Santiago-Ávila, Washington Wildlife First’s science and advocacy director, said they are poring through a trove of documents received from the department “that will help expose the selective, vindictive, and defamatory nature of this campaign to oust pro-wildlife commissioners. You will be hearing a lot more about this from us in the coming days and weeks.”

Smith said in a statement Friday that when she first read the memo, “I was shocked to see the false and outrageous claims it contained, and even more so when I found out that it was written by an attorney.”

“But after I reviewed it more carefully and compared it to other documents, the pieces began to fall together, and I realized that it reveals a lot about what department management has been doing behind closed doors over the past year,” she said. “I am not going to comment further until I consult with my attorneys and decide upon my next course of action.”

A serious soap opera

Much of the commission’s strife can be traced to its controversial decision in November 2022 to stop recreational hunting of black bears in the spring.

Sportsmen’s Alliance, an Ohio-based organization, opposed the decision. Convinced commissioners misbehaved throughout the process, it sought their emails, texts and other communications to figure out if, in fact, they had failed to follow state law concerning the conduct of public meetings and preserving public records.

It took a lawsuit, but the group eventually received thousands of records in 2025.

On May 16, 2025, the group filed a petition asking Ferguson to remove commissioners Smith, Rowland, Barbara Baker, and John Lehmkuhl, alleging misconduct and malfeasance. They included some of the obtained records. Ferguson has not commented or acted on the petition.

Ten days earlier, Susewind had two boxes of records generated from the hunters’ group’s request delivered to Thomas Knoll Jr., the agency’s criminal justice legal liaison for law enforcement.

“Initial review of these documents raises concern regarding potential inappropriate conduct by several Fish and Wildlife Commissioners,” Susewind wrote Knoll on May 8. “I would like your independent assessment of the materials provided including a written opinion on whether the records indicate inappropriate conduct.”

Knoll submitted his memo on May 16 and Susewind shared a copy with Ferguson’s staff.

On June 20, the Office of Financial Management signed a contract with Chiedza Nziramasanga of Transformative Workplace Investigations to “provide a comprehensive investigation of a reported experience in a work unit to allow leadership to determine if any discrimination, retaliation and/or other policy violations occurred as alleged.”

It would not be until mid-August before Ferguson publicly acknowledged this investigation into the commission. He waited to do so until after Susewind formally asked him to look into the situation on Aug. 5.

The Knoll memo, along with the Sportsmen’s Alliance petition, was in the initial batch of documents provided to the investigator.

“This can be a good starting point to understand the issues that DFW had flagged,” Franklin Plaistowe, chief operations officer for Ferguson, wrote in an email to Nziramasanga.

Transformative Workplace Investigations was to turn in its final report on Friday, Feb. 13, but has received a one-month extension.

Susewind said he didn’t make the memo public last year because he did not want to “inadvertently bias that investigation.” He said commissioners could have seen it and all the other records generated from the Sportsmen’s Alliance request if they wanted.

“We did offer to go over documents with all commissioners both before and after the Thomas Knoll memo,” he said this week.

Commission chair Jim Anderson agreed.

“I was aware of it. I think we all had an opportunity to know what’s there,” he said Thursday.

Rowland and Smith said they don’t recall such an offer.

“I most definitely did not see it,” Smith said.

‘Have each other on speed dial’

Soon after taking office, Ferguson withdrew two Inslee administration appointments to the commission. Materials obtained from the computer of one of those appointees, former commission vice chair Tim Ragen, steered Knoll’s attention to commissioners Smith and Rowland and Washington Wildlife First’s Davis.

Knoll contends the commissioners failed to recognize the importance of retaining records and did not promptly respond to records requests, including those involving commission-related communications made on personal devices.

Some of his sharpest critiques are directed at the relationship between Davis and Smith, Rowland and Ragen. He said they appeared to “have each other on speed dial.” They met regularly, often before commission meetings, and Davis corresponded directly with each, he noted, raising the spectre of potential conflicts of interest.

When Ferguson walked back Ragen’s appointment, Washington Wildlife First was among the groups that pressed the governor to keep him on the commission.

Knoll cited one email from 2023 where Davis invited commissioners to ask questions about a lawsuit she filed against the state agency on behalf of two clients.

“The record does not show what was discussed about the pending lawsuit, but this type of communication is clearly inconsistent,” with the commission rule to not engage in any activity which gives rise to the appearance of a conflict of interest, he wrote.

Rowland, an attorney, flatly denied discussing litigation against the department with Davis “or any other attorney for a party in litigation” with the agency.

Davis, in her statement, said her discussions with commissioners were “an appropriate, ethical, and protected exercise of my First Amendment right to speak to government officials on matters of public importance.”

Washington State Standard is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Washington State Standard maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Bill Lucia for questions: info@washingtonstatestandard.com.